The ancient wisdom of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras offers more than just physical postures. It presents a comprehensive system for personal transformation and spiritual growth. This classical text, compiled around 400 CE by the sage Patanjali, outlines an eight-limbed path known as Ashtanga Yoga that guides practitioners toward inner peace and self-realization.

Unlike modern yoga that often focuses primarily on physical poses, Patanjali’s system addresses every aspect of human existence—from ethical behavior to breath control to deep meditation. By following this path, students develop not only physical strength and flexibility but also mental clarity, emotional balance, and spiritual awakening.

Historical Context

The Yoga Sutras were composed during a period when various philosophical schools were flourishing in India. Patanjali systematized existing yogic knowledge into 196 concise aphorisms (sutras) that have guided spiritual seekers for centuries. The text belongs to one of the six classical schools of Indian philosophy (darshanas) known as Yoga darshana.

While historians debate Patanjali’s exact identity and timeline (with estimates ranging from 500 BCE to 400 CE), his contribution has remained relevant across cultures and time periods, offering practical wisdom for modern practitioners.

This article explores each branch of Patanjali’s Ashtanga Yoga, examining its purpose, effects, and significance in both traditional and contemporary contexts. Whether you’re a serious yoga student, researcher, or simply curious about ancient wisdom, understanding this systematic approach provides valuable insights into the full potential of yogic practice.

The Foundation and Philosophy of Patanjali’s Yoga

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras present a philosophical framework that views human suffering as stemming from ignorance about our true nature. According to this system, we mistake our changing thoughts, emotions, and sensations for our essential self, creating attachment and aversion that lead to pain. Yoga offers a methodical path to remove this misperception.

The text begins with “atha yoga anushasanam” – “now, the teachings of yoga begin.” This opening sets the stage for a practical approach rather than mere theoretical knowledge. Patanjali defines yoga as “chitta vritti nirodha” – the cessation of the fluctuations of the mind. When mental activity settles, we rest in our true nature as pure awareness.

The Yoga Sutras contain four chapters (padas): Samadhi Pada introduces the aim of yoga and types of mental modifications; Sadhana Pada describes the practices; Vibhuti Pada explores the powers that develop through practice; and Kaivalya Pada examines the nature of liberation.

Core Philosophical Concepts

Patanjali’s system incorporates ideas from Samkhya philosophy, including the distinction between purusha (pure consciousness) and prakriti (matter, including mental activity). The goal of yoga is to recognize this difference, freeing consciousness from identification with changing mental states.

The text also explains five kleshas (afflictions) that cause suffering: avidya (ignorance), asmita (ego-identification), raga (attachment), dvesha (aversion), and abhinivesha (fear of death). These act as obstacles on the yogic path and are gradually removed through systematic practice.

Unlike many philosophical systems that remained abstract, Patanjali’s genius was in creating a step-by-step method that gradually transforms consciousness. This eight-limbed approach (Ashtanga) begins with external behavior and progressively moves inward toward subtler dimensions of awareness. Each stage prepares the student for the next, creating an integrated path to spiritual freedom.

The Eight Limbs: An Overview of Ashtanga Yoga

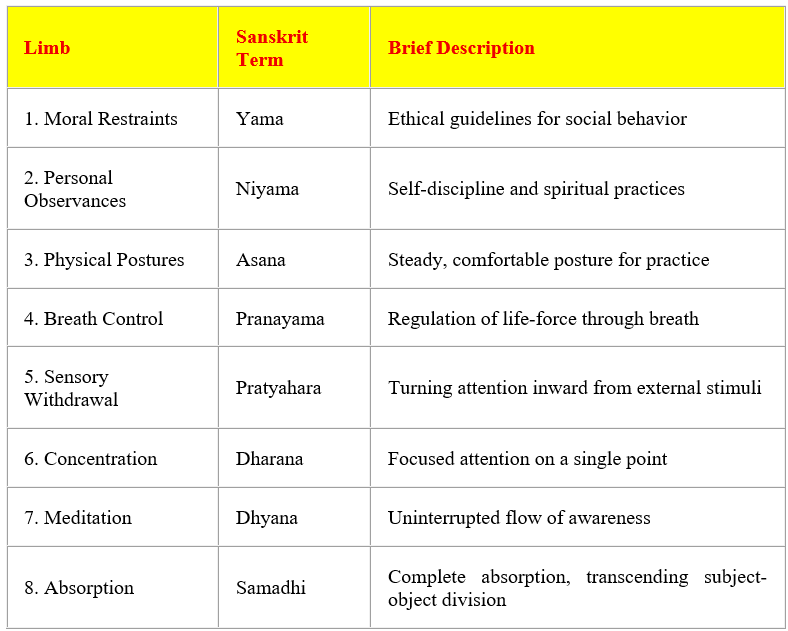

Ashtanga Yoga presents a structured pathway for comprehensive human development. “Ashta” means eight and “anga” means limb, describing the eight components that work together as an integrated system. Each limb builds upon the previous one, creating a progressive journey from external to internal practices.

These eight aspects address every dimension of human experience—ethical, physical, energetic, psychological, and spiritual. They create a balanced approach that recognizes the interconnection between how we live, move, breathe, and direct our awareness. Rather than focusing only on physical fitness or mental concentration, this holistic system transforms the entire being.

The first four limbs (yama, niyama, asana, pranayama) constitute the external practices (bahiranga yoga) that prepare the body and mind. The next two (pratyahara and dharana) form the internal practices (antaranga yoga) that develop mental control. The final two (dhyana and samadhi) represent the culmination (antaratma yoga) leading to self-realization.

1. Yama: The Five Moral Restraints

The first limb of Ashtanga Yoga lays the foundation for the entire practice through ethical guidelines for social interaction. Yama refers to universal moral principles that govern our relationship with others and the external world. These restraints are not merely rules but reflections of our true nature when we remove the veil of ignorance.

Patanjali outlines five yamas that help practitioners minimize harm and create harmonious relationships. These principles are considered universal across cultures, religions, and time periods. They address the most common ways humans create suffering for themselves and others through harmful actions.

a. Ahimsa: Non-violence

Ahimsa forms the cornerstone of yogic ethics, extending beyond physical harm to include emotional and mental forms of violence. This principle encourages compassion toward all beings, including oneself. When firmly established, ahimsa transforms our relationship with the world as we recognize the interconnection between all life forms.

Research suggests that practicing non-violence improves psychological wellbeing by reducing hostility and increasing empathy. A 2019 study published in the Journal of Positive Psychology found that participants who practiced compassion meditation showed reduced aggressive responses and increased prosocial behavior compared to control groups.

b. Satya: Truthfulness

Satya involves honesty in speech, thought, and action. More than avoiding lies, this principle asks us to speak with both accuracy and kindness. The Yoga Sutras suggest that when truthfulness is perfected, our words become increasingly powerful and effective.

In daily practice, satya requires discernment about when and how to express truth. When truth might cause unnecessary harm, the practitioner considers whether speaking is appropriate—balancing truthfulness with non-violence. This principle develops integrity and clear communication that builds trust in relationships.

c. Asteya: Non-stealing

Asteya extends beyond not taking material possessions to include subtler forms of theft—taking credit for others’ ideas, consuming more than we need, or wasting others’ time. This principle addresses greed and the sense of lack that drives it, cultivating contentment and respect for boundaries.

The yama encourages fair exchange and gratitude for what we receive. Some yoga scholars suggest that established asteya brings material abundance, not through magical thinking but because trustworthiness and generosity naturally create positive relationships and opportunities.

d. Brahmacharya: Right Use of Energy

Often translated as “celibacy,” brahmacharya more broadly refers to the wise management of vital energy. In classical traditions, this sometimes meant sexual abstinence for spiritual aspirants, but modern interpretations focus on moderation and conscious choices about how we expend energy.

Practicing brahmacharya involves directing energy toward spiritual growth rather than depleting it through excessive sensory indulgence. This principle encourages the question: “Does this activity drain or enhance my vitality?” Contemporary practitioners apply this to various aspects of life, including relationships, media consumption, and work habits.

e. Aparigraha: Non-possessiveness

Aparigraha addresses our tendency to accumulate and cling to possessions, people, and identities. This principle encourages taking only what we need, letting go of excess, and recognizing the temporary nature of all things. Freedom from attachment brings lightness and contentment.

2. Niyama: The Five Personal Observances

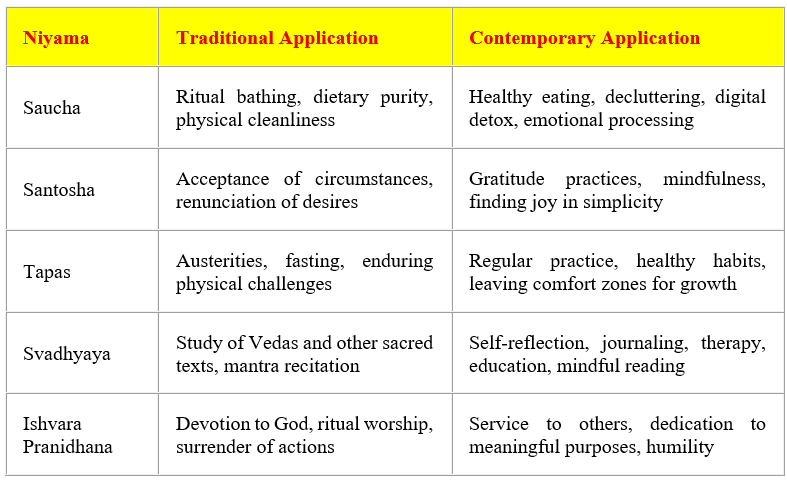

The second limb of Ashtanga Yoga, niyama, shifts the focus from external relationships to personal discipline and self-care practices. These five observances cultivate positive habits that support spiritual growth and create an internal environment conducive to yoga. While yamas address what we should avoid, niyamas guide what we should actively develop.

These personal practices help transform daily routines into opportunities for growth and refinement. They create rhythm and purpose in everyday life, turning ordinary activities into meaningful practices. Through consistent application, the niyamas develop qualities that support deeper stages of yoga.

a. Saucha: Cleanliness

Saucha encompasses both external cleanliness of body and environment and internal purity of mind and emotions. Physical practices include regular bathing, clean eating, and maintaining orderly surroundings. Mental aspects involve clearing negative thoughts and emotions through meditation, pranayama, and self-reflection.

b. Santosha: Contentment

Santosha involves cultivating satisfaction with what we have rather than constantly craving more. This doesn’t mean abandoning healthy ambition but finding peace in the present moment regardless of external circumstances. The practice develops resilience and an internal sense of sufficiency.

c. Tapas: Self-discipline

Tapas literally means “heat” or “austerity” and refers to the disciplined effort that purifies and transforms. This includes regular practice despite obstacles, willingness to face discomfort for growth, and the heat of transformation that occurs through dedicated effort. Tapas builds willpower and resilience.

d. Svadhyaya: Self-study

Svadhyaya traditionally includes study of sacred texts and reflection on their meaning for one’s life. In broader application, it encompasses all forms of self-knowledge—observing patterns in thoughts and behaviors, examining motivations, and learning through both formal study and life experience.

e. Ishvara Pranidhana: Surrender to the Divine

The final niyama involves surrender to something greater than the individual ego. Depending on one’s perspective, this might be conceptualized as devotion to God, alignment with universal consciousness, or dedication to the highest good. This practice releases the limitations of self-centered thinking.

Together, the niyamas create a foundation of positive habits and attitudes that prepare the practitioner for deeper aspects of yoga. They transform daily life into a laboratory for spiritual growth, bringing mindfulness and purpose to routine activities. When firmly established, these observances generate the inner conditions necessary for successful meditation practice.

3. Asana: The Cultivation of Steadiness and Ease

In Patanjali’s system, asana refers to the physical posture adopted for meditation rather than the varied physical poses of modern yoga. The Yoga Sutras describe asana briefly but profoundly: “sthira sukham asanam,” meaning the posture should be both steady (sthira) and comfortable (sukham). This balance between stability and ease creates the ideal foundation for the inner practices of yoga.

The primary purpose of asana in Patanjali’s system is to prepare the body to sit comfortably for meditation. A stable, comfortable posture allows practitioners to remain still for extended periods without distraction from physical discomfort. When the body is steady, attention can turn inward toward subtler aspects of practice.

The Evolution of Asana Practice

While Patanjali mentions only the seated meditation posture, later yoga traditions developed numerous physical poses to prepare the body for meditation. These practices evolved to address common obstacles like stiffness, weakness, and energy imbalances that hindered comfortable sitting. Hatha yoga texts like the Hatha Yoga Pradipika (15th century CE) describe various asanas and their benefits.

Modern postural yoga, with its emphasis on physical alignment and movement, represents a further evolution of these preparatory practices. Contemporary approaches often combine traditional wisdom with modern understanding of anatomy and physiology. However, Patanjali’s core principle remains relevant—the goal is to develop a body-mind connection characterized by both steadiness and comfort.